Cervical Effacement: A Sign That Labour Has Begun

While you’re preparing mentally and emotionally for the birth of your baby, your body is also getting ready physically. In the earliest, ‘latent’, phase of labour your cervix starts getting ready to open in preparation for delivery. Cervical effacement (thinning) and dilation (opening) are important parts of this process. Read more about their role in childbirth so you can better understand the amazing things your body does to help you give birth.

What Is Cervical Effacement?

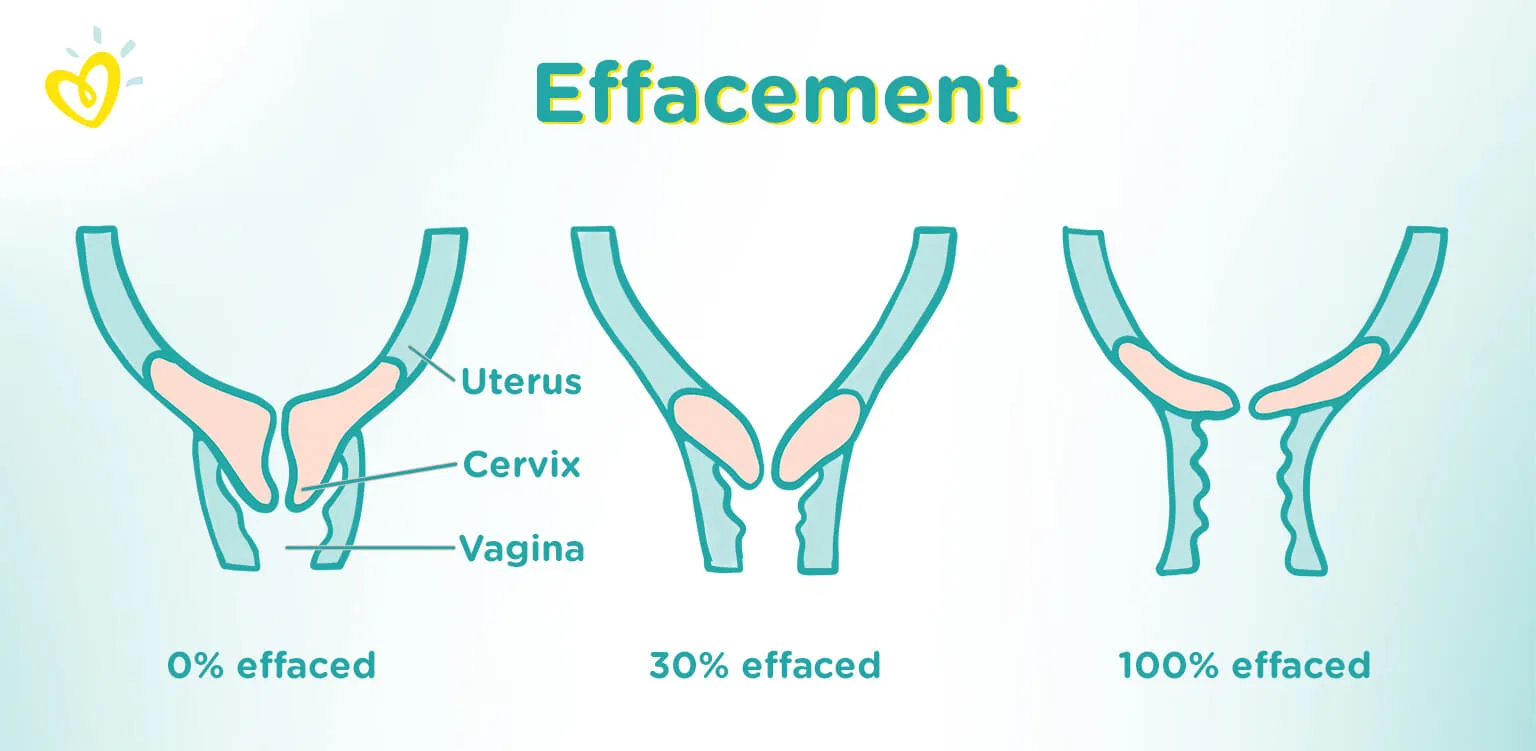

To properly understand the meaning of cervical effacement, it's worth going over some anatomy. Your cervix is the long, narrow end of the uterus – otherwise known as the ‘neck’ or ‘entrance’ of the uterus – that is basically the gateway between the uterus and vagina.

Of course, for your baby – if you have a vaginal birth – it will be the exit! But before that happens it needs to open.

Normally, your cervix is firm and closed. In the early stage of labour – known as the ‘latent’ phase, the cervix starts to soften and thin out.

This thinning process is called effacement. It’s measured in percentages from 0 to 100 percent, the latter of which means your cervix is fully effaced. In other words, being 100 percent effaced means you are fully effaced.

Your midwife or obstetrician can determine how effaced you are with a vaginal exam. It’s not anything that you yourself can check, and nor is it something you need to worry about – your midwife and doctor will be keeping an eye on it for you.

What Does It Mean to Be 50 Percent Effaced?

If you’re being examined during labour, your midwife or doctor might say something like ‘You’re 50 percent effaced’. This just means that your cervix has thinned out by 50 percent of what is considered fully effaced. So, if you hear this, you’re halfway to 100 percent effacement.

The same applies to all the different degrees of effacement. For example, if you’re 80 percent effaced, the thinning of your cervix is 80 percent complete and you’re nearing 100 percent – or full – effacement.

What Is the Difference Between Cervical Effacement and Dilation?

Unlike effacement, which is when your cervix shortens and thins out (measured in percentages), dilation is the term used to describe the opening or widening of the cervix. This is measured from 0 to 10 centimetres, the latter of which means you’re fully dilated.

During labour, your midwife and/or obstetrician will check both effacement and dilation to see how far along you are.

What Is the Latent Phase of Labour?

To properly understand the meaning of effacement, you need to know a bit about the first stage of labour, which is broken up into two phases, known as the latent phase and the active phase of labour.

The Latent Phase of Labour

This is the earliest stage of labour.

During your pregnancy, you may experience Braxton Hicks contractions , which are often called ‘practice’ or ‘false’ contractions, but in the latent phase of labour, you will start feeling proper or ‘true’ contractions.

Unlike Braxton Hicks, true contractions can be painful, and they occur at regular intervals. However, during the latent phase of labour you may experience contractions stopping and starting, with some bouts lasting a few hours at a time.

If you aren’t sure whether you’re having true labour contractions, try timing them. If they come at regular intervals, they’re probably the real deal. If you’re still unsure, ask your midwife or doctor.

The latent phase of labour is also when your cervix starts softening and thinning (effacement) and opening (dilation). This process continues, often very slowly, until you are in active labour, when the pace of effacement and dilation speeds up.

Let your midwife know if you start feeling contractions or any other signs of labour, which in the latent phase might include:

The length of the latent phase of labour differs a lot between mums-to-be and pregnancies. It could last anything from a few hours to a several days. Usually, your midwife will advise you to stay at home and try to relax until the active phase of labour starts.

Some of these comfort measures might be useful for helping you cope with the contractions and other labour symptoms both during the latent and active phases of labour.

Active Labour

The active phase of the first stage of labour usually starts when the cervix has dilated to around three to four centimetres and is fully effaced. By this time, the contractions will be getting progressively stronger and closer together.

The active phase usually lasts until the cervix is fully dilated (10 centimetres). If you’re giving birth vaginally, this is when the next stage of labour – the actual delivery of your baby – can begin.

Your midwife will be able to give you personalised advice on when to leave for the hospital or birthing centre. As a general rule, once your contractions are regular and three or four minutes apart – at the latest – it’s almost certainly time to grab your hospital bag and head for the door.

FREQUENTLY ASKED QUESTIONS

The Bottom Line

Effacement isn’t an obvious sign of labour that you’ll be looking out for, but it is a physical change that gives your midwife and doctor important information about how far along your labour is.

Although it’s good to know as much as you can about all the ins and outs of labour and childbirth, it’s also reassuring to know that the professionals looking after you are on top of these kinds of details, so you can stay focused and relaxed.

It won’t be long before you finally get to meet your little one, and that’s what matters the most.

How we wrote this article The information in this article is based on the expert advice found in trusted medical and government sources, such as the National Health Service (NHS). You can find a full list of sources used for this article below. The content on this page should not replace professional medical advice. Always consult medical professionals for full diagnosis and treatment.

Read more about Pregnancy

Related Articles

Join Pampers Club and get: